Forgotten Order: Why Self-Organization Is Not Informal Chaos

A Blog Essay for URBAN STEPS

“It was not absence that

structured these neighborhoods, but presence—of

responsibility, reciprocity, and embedded social control.”

Zahra Breshna, Kabul fieldnotes, 2004

Introduction

In the fast-growing cities of

the Global South, self-organization is often misunderstood—reduced

to informal housing, market improvisation, or administrative failure. But what

if these structures represent not a lack of order, but another kind of order

altogether?

Drawing on urban studies in

Kabul’s historic neighborhoods, this essay revisits the concept of

self-organization not as resistance to planning, but as an inherited system of

coexistence and regulation—a “forgotten order” deeply rooted in

cultural norms, moral obligations, and spatial practice.

Coexistence

Before the State

Before centralized

administrations took hold, urban regulation in cities like Kabul was governed

through a layered ecology of responsibilities:

- wokil guzar (neighborhood representatives) mediated conflict

- guilds managed price

stability and trade

- mosques and

community elders organized care, safety, and sanitation

- property norms were negotiated

through shared memory and moral obligation.

“Mechanisms of distribution in

the alleys of Kabul did not primarily follow formal state directives but rather

a social code that was based on fair use, respect, and reputation.”

Zahra

Breshna, Kabul fieldnotes, 2004

These systems evolved through practice, negotiation, and collective ethics,

forming a governance architecture both durable and dynamic.

From

Regulation to Respect

This form of cultural

regulation was never just about efficiency. It relied on “honor economies”—trust,

reputation, and intergenerational learning. This is what allowed these

neighborhoods to function even in the absence of external control.

Self-organization, then, was not unplanned—it was differently planned.

This makes it distinct from

what today is labeled “informal.” While informality often reflects survival in the absence

of access, self-organization is

an inherited framework. It imposes duties, not just rights. It is neither

romantic nor nostalgic—it

is demanding, participatory, and deeply relational.

What

We Lost (And Can Learn)

Today, urban development

programs often mistake self-organization for administrative failure—or

attempt to replace it with participation models that ignore the power of

embedded norms.

“Planners tend to treat

community as a resource to be activated, not as a governance system already in

place.”

Zahra Breshna, Kabul fieldnotes, 2004

By failing to recognize this, we overlook what cities

already know how to do.

URBAN

STEPS and the Return of Memory

URBAN STEPS does not

seek to idealize self-organization, but to learn from it. We explore how these

forms of “cultural cohabitation” might

support more inclusive, flexible planning—especially in areas where state

presence is limited.

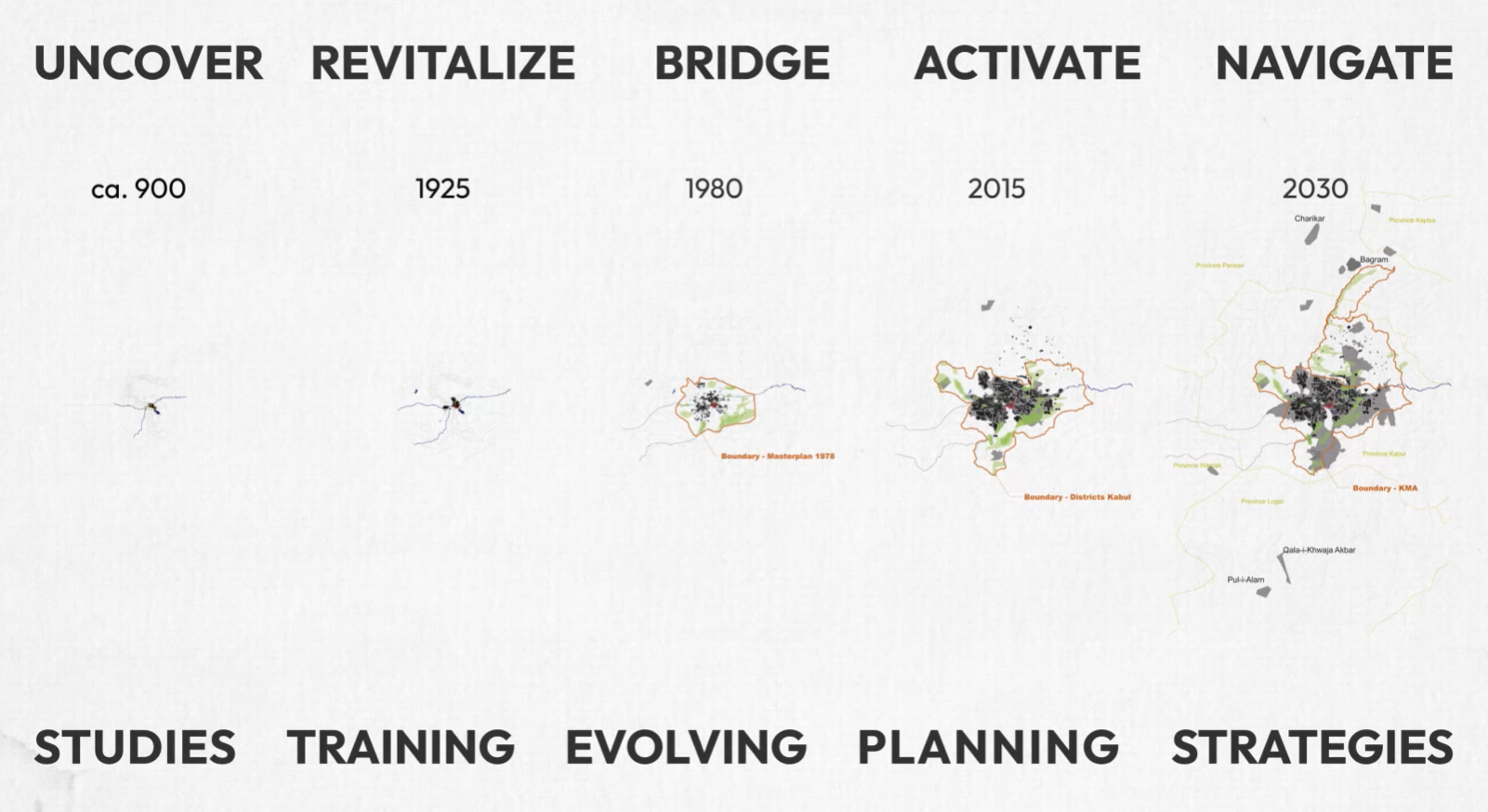

Our methods Uncover/Study (U/S) and Bridge/Activate (B/A) draw directly on these field studies: historical maps, neighborhood surveys, and the living memory of street-level planning. Through this lens, we understand cities not only as challenges to be governed, but also as systems that have long governed